This is the fifth in a series of posts I am sharing on plant based nutrition. I have personally enjoyed a plant based diet for close to ten years. Some of which have been as a vegetarian, and some as vegan. I have experienced numerous deficiencies during my journey, partly due to malabsorption, though I believe a lack of education was at the heart of it all. Yes, you can be healthy and well on a conscious and compassionate diet – but it takes careful planning and awareness of what your own unique body needs.

[bctt tweet="Get enough quality protein on a plant-based diet. Learn more here."]

What you need to know

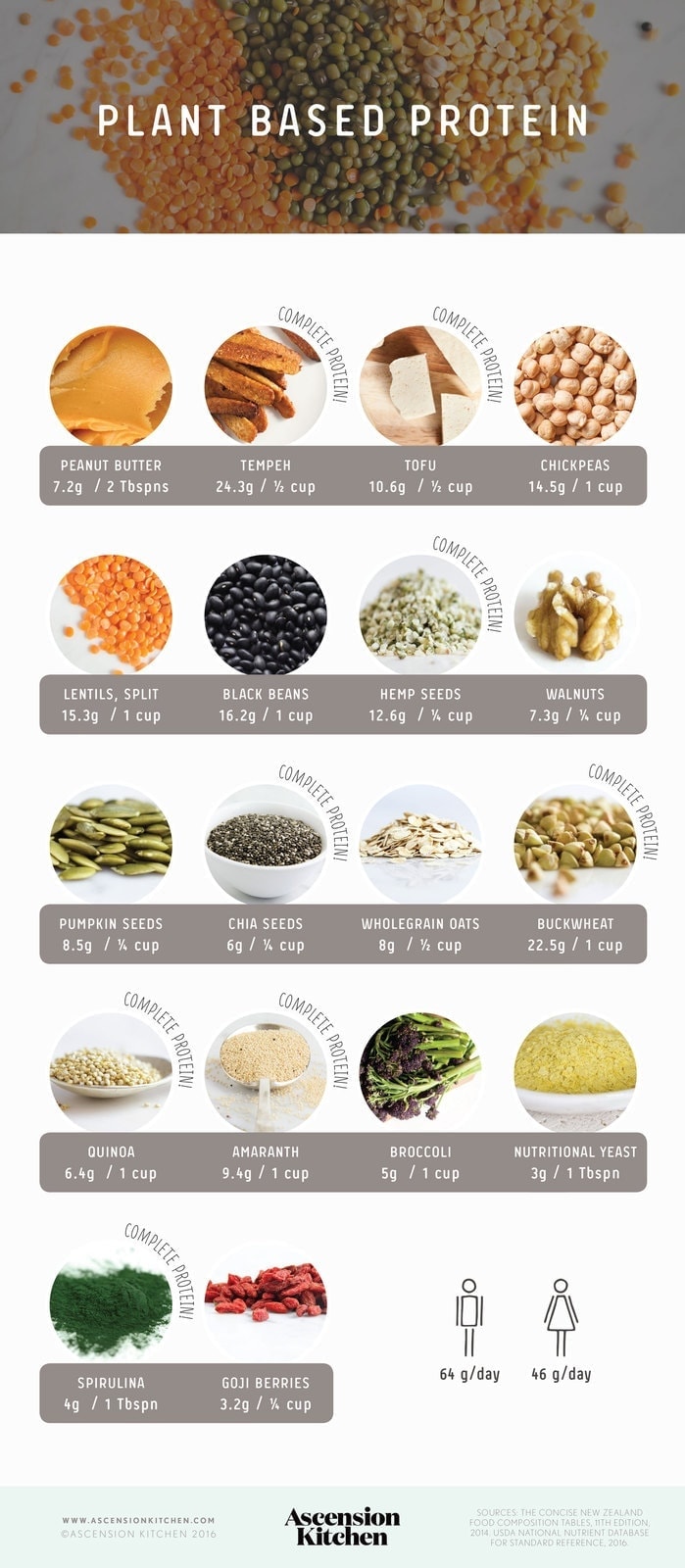

Proteins are made up of individual amino acids, and are the main building blocks of the body. Plant based diets provide ample protein providing the diet is varied and balanced. It is true that for the most part, plant proteins are not complete – meaning there is one or more limiting amino acid (for example lysine in grains and methionine in legumes), however it is a myth that these foods must be combined like once thought. In actuality – there are quite a number of complete plant proteins available to us – these include soy (organic is best!), spirulina, hemp and chia seeds, and the gluten free grains; buckwheat, quinoa and amaranth. Favouring plant proteins over animal proteins is associated with a lower risk for many chronic diseases, such as heart disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

RDI:

64 g/day for adult men (19-70 yrs)

46 g/day for adult women (19-70 yrs)

These RDI’s are based on 0.84 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for men, and 0.75 grams per kilogram of body weight per day for women. The RDI is higher for those with greater protein needs – infants, children, pregnant and lactating women, and those over the age of 70 [1].

Although there is no set upper limit for protein intake, more is not necessarily better. Firstly, consuming large quantities of protein will naturally displace and crowd out other important nutrients from foods, and secondly, some studies suggest excess intake may lead to osteoporosis and kidney disease [2]. However, the issue of bone and kidney health in relation to high-protein diets is controversial and as yet, inconclusive.

For the full list of recommendations by life stage and gender, including pregnancy and lactation, visit the Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand here.

[3].

Introduction

Proteins are the most important biological compounds. They’re essential for every single living cell in the body – all 37.2 trillion of them. Over 40% of protein is found in our muscles, 25% or more is found in our internal organs, and the rest is found mostly in skin and blood [2].

They make up the structural component of the human body (the skeleton, connective tissue, muscle and skin), and hormones such as insulin and human growth hormone. They make up enzymes (substances responsible for facilitating all biochemical reactions in the body), they perform transportation duties (think haemoglobin – the protein that carries oxygen around the blood to tissues), they have a role in immune health, protecting against disease (think the formation of antibodies against foreign antigens), they help our blood clot (think the clotting protein fibronectin), they store materials (think how the protein ferritin stores iron in the liver), and they regulate the expression of genes [4].

Proteins can also be used by the body for fuel, but it is not the preferred energy source. With insufficient glucose, protein will be sacrificed – tissue proteins and muscle mass will be broken down in order to make amino acids available for energy or glucose production [1].

What are proteins made of?

Proteins are made from chains of individual amino acids linked together with peptide bonds. They can be assembled in any number of combinations (in fact, it is thought that there are over 100,000 different proteins in the body!), and can be as short as two – or as long as several hundred [1, 4].

Essential, non-essential and conditional amino acids

Of the 20 amino acids used to build proteins (there are many more non-protein forming amino acids), nine are essential to our diets as the body can’t produce them endogenously. These include;

- Histidine

- Isoleucine

- Leucine

- Lysine

- Methionine

- Phenylalanine

- Threonine

- Tryptophan

- Valine

Additionally, there are 11 non-essential amino acids that the body can synthesize itself:

- Alanine

- Arginine

- Asparagine

- Aspartic acid

- Cysteine

- Glutamic acid

- Glutamine

- Glycine

- Proline

- Serine

- Tyrosine

Sometimes, some of the non-essential amino acids become conditionally essential. This occurs when their synthesis is impaired (either due to a lack of precursor amino acids or impaired conversion), particularly during times of rapid growth, illness, extreme stress or trauma (for example, after a surgery, or if an organ fails to function properly). As an example, the body will use the essential amino acid phenylalanine to make the non-essential amino acid tyrosine, but if that precursor is unavailable (for example, not provided by the diet), then tyrosine becomes conditionally essential [1, 2].

Where do we get amino acids?

Amino acids come from proteins – our bodies produce some, and our diet provides the rest.

Animal sources of protein include meat, fish, poultry, eggs and dairy. Plant sources of protein include legumes, nuts and seeds, grains and vegetables.

Complete proteinS

The term complete protein refers to a food source that provides all of the nine essential amino acids in approximate amounts needed by the human body [2].

Meat, fish and poultry are complete proteins. For vegetarians – eggs, milk, yoghurt and cheese also provide complete proteins. Gelatin however is not complete – it lacks the essential amino acid tryptophan [2].

For the most part, plant foods are not complete protein sources, though there are some exceptions:

- Soy (including organic tofu, tempeh and edamame beans) [2]

- Spirulina [5]

- Hemp seeds [6]

- Chia seeds [7]

- Quinoa [8]

- Buckwheat [9]

- Amaranth [10]

Typically though, plant foods seem to have too little of one or more essential amino acids to be termed a complete protein. The amino acid that is lacking is termed a limiting amino acid [2].

In whole grains, lysine is the limiting amino acid. In legumes, it is methionine. Cultures around the world have traditionally eaten both these food groups together – for example, rice and beans in Mexico, or rice with chickpeas or lentils in India. If you are on a vegan diet, you will need to ensure you are consuming both these food groups in order to receive all the essential amino acids your body needs to build proteins. Those on a purely raw foods diet would be limiting their lysine and methionine intakes – but particularly methionine, as there are very few legumes you can consume raw.

Protein combining myth busting

It was once thought that you must consume plant sources of proteins with limiting essential amino acids at the same meal, however, the body actually contains a pool of essential amino acids, which can be used to complement proteins received from the diet. Recent literature tells us that combining proteins (mixing grains with legumes for example) at the same meal is unnecessary – the important thing is to simply meet energy needs and consume a variety of plant foods each day [11].

Protein quality

Based on the above, a complete protein is considered a quality protein since it provides the nine essential amino acids in relevant amounts. Conversely, incomplete proteins are considered of low quality. Several methods have been developed in order to assess protein quality, these include the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS), the Protein Efficiency Ratio, and the Chemical or Amino Acid Score, amongst others [2].

The PDCAAS evaluates the protein quality of a food, based on our amino acid requirements and ability to digest the food [11]. This method has been adopted by the World Health Organisation as the preferred way to measure protein values in human nutrition [12].

According to the PDCAAS, most animal proteins have a perfect or near perfect score of 1.0 [11], with a digestibility of 90 to 99% [1]. Plant proteins are less digestible at 70 to 90%, soy and legumes being the exceptions [1]. This may lead some to believe strict vegans may require more dietary protein – however there are currently no government recommendations [14]. This is likely due to lack of studies on this group of the population.

Are vegetarians and vegans meeting their daily protein needs?

According to the EPIC-Oxford study – one of the largest studies on vegetarians in the world, vegans had by far the lowest intakes of protein (also, zinc, calcium, retinol, vitamin B12 and vitamin D) compared to vegetarians, meat and fish eaters [13]. The table below shows you what percentage protein contributed to the total food energy of subjects studied.

Mean daily protein intake amongst diet groups [13]:

|

|

Men: |

Women: |

|

Meat-eaters |

16% |

17.3% |

|

Fish-eaters |

13.9% |

14.9% |

|

Vegetarians |

13.1% |

13.8% |

|

Vegans |

12.9% |

13.5% |

|

Recommended protein intake (as a % of total food energy) |

15-25% [11] |

15-35% [11] |

You will note that the recommended percentage of food energy from protein is between 15-25% of total energy [11], however the US and Canadian Recommended Dietary Allowances have actually set their lower level of intake at about 10-11%. Whilst you may only need to consume 10% of your total energy from protein in order to provide for the body’s basic needs, this would not be enough to be meeting the estimated average requirements for your micronutrients [14]. By these standards, vegetarian and vegan men and women surveyed in the EPIC-Oxford study have deficient intakes.

When looking at local studies on Australian populations, findings are similar to that presented in the above study: Australian vegetarian women were found to have a significantly lower protein intake than their omnivore counterparts [15].

However – this may be due to poor diet planning as it is in fact quite achievable to meet protein needs with plant proteins.

Plant protein has health benefits

Favouring plant protein over animal protein may be doing your health a world of good, particularly in regards to reducing your risk of chronic disease.

Based on data analysed from a nationwide nutrition survey in the US (with a sample size of over 13,500), meat consumption has been positively associated with obesity – particularly abdominal obesity [16]. More recently (2015), a nationwide survey on cardiovascular risk factors in Luxembourg came to similar conclusions, stating a lowered animal protein intake may be important for maintenance of healthy body weight [17].

Higher plant protein intakes have also been shown in studies to be protective of both metabolic syndrome [18] and type 2 diabetes [19, 20], and are inversely associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. On the other hand, high animal protein intake is positively associated with cardiovascular mortality [21].

[bctt tweet="Plant protein is associated with lower mortality. How to include more in your diet here."]

How to get more protein into your plant based diet:

Below is a table of plant based sources of protein, and their protein content per average serving size. It is a good idea to aim to include a serving of plant protein (or vegetarian protein such as eggs) with every meal.

|

Food |

Protein per 100g |

Protein per serving |

|

Legumes |

|

|

|

Peanut butter |

28.8g |

2 tablespoons = 7.2g |

|

Tempeh |

18.5g |

½ cup = 24.3g |

|

Soybeans, cooked* |

12.35g |

½ cup = 11.1g |

|

Black beans, cooked |

8.9g |

1 cup = 16.2g |

|

Chickpeas, cooked* |

8.86g |

1 cup = 14.5g |

|

Tofu |

8.1g |

½ cup = 10.6g |

|

Red kidney beans, cooked |

7.9g |

1 cup = 14.2g |

|

Lentils, split, cooked |

7.6g |

1 cup = 15.3g |

|

Green peas |

5.4g |

½ cup = 4.5g |

|

|

|

|

|

Nuts and Seeds |

|

|

|

Hemp seeds, hulled* |

31.56g |

¼ cup = 12.6g |

|

Walnuts |

25.7g |

¼ cup = 7.3g |

|

Pumpkin seeds |

24.6g |

¼ cup = 8.5g |

|

Pine nuts |

24g |

¼ cup = 9.6g |

|

Sunflower seeds |

22.8g |

¼ cup = 6.4g |

|

Almonds |

21.2g |

10 nuts = 2.5g |

|

Pistachios |

20.6g |

¼ cup = 6.7g |

|

Cashews |

17g |

¼ cup = 6g |

|

Chia seeds* |

16.5g |

¼ cup = 6g |

|

Hazelnuts |

14.8g |

¼ cup = 5g |

|

Brazil nuts |

12g |

10 nuts = 4.5g |

|

|

|

|

|

Whole grains (gluten free) |

|

|

|

Wholegrain Oats |

14.3g |

½ cup = 8g |

|

Buckwheat* |

13.25g |

1 cup = 22.5g |

|

Sorghum* |

10.62g |

1 cup = 20.4g |

|

Quinoa, cooked |

4.3g |

1 cup = 6.4g |

|

Wild rice, cooked |

4.1g |

1 cup = 7g |

|

Amaranth, cooked |

3.8g |

1 cup = 9.4g |

|

Brown rice, cooked |

2.6g |

1 cup = 5.3g |

|

|

|

|

|

Vegetables |

|

|

|

Globe artichoke, cooked |

3.5g |

1 artichoke = 4.2g |

|

Brussel’s sprouts, steamed |

3.4g |

1 cup, quartered = 4.4g |

|

Broccoli, cooked |

3g |

1 cup = 5g |

|

Cauliflower, cooked |

1.9g |

1 cup = 2.6g |

|

Leek, cooked |

1.8g |

1 cup = 2.4g |

|

Pumpkin, baked with oil |

1.8g |

1 cup = 2.3g |

|

Spinach, raw |

2.5g |

1 cup = 1.1g |

|

|

|

|

|

Other |

|

|

|

Nutritional yeast* |

60g |

1 tablespoon = 3g |

|

Spirulina* |

57.47g |

1 tablespoon = 4g |

|

Nori seaweed sheets |

38.8g |

5 sheets = 4.4g |

|

Sunwarrior Protein Powder (Natural) |

- |

1 scoop = 17g |

|

Goji berries* |

14.26g |

¼ cup = 3.2g |

Note:

¼ cup = 4 tablespoons • ½ cup = 8 tablespoons • 1 cup = 16 tablespoons

Sources:

The Concise New Zealand Food Composition Tables (11th ed.), 2014.

*USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, 2016.

Note: avocado on toast won’t cut it!

As you can see from the above table, there is plenty of protein to be found in plant foods, however – you actually have to eat them in order to meet your needs! For example, if cereal, fruit based smoothies and avocado on toast make regular appearances on your kitchen table at breakfast, try adding a protein booster to make them a more balanced meal. Some practical ideas include an egg (for vegetarians), some baked beans, a few tablespoons of nuts and seeds (particularly hemp and chia), or even a scoop of quality protein powder (there are some great ones on the market at the moment that are made from sprouted grains, they’re very gentle on the digestive tract).

As an added bonus, a recent meta-analysis of studies found protein increases fullness [22], so if you include some with your breakfast each day, you will be less likely to reach for that sugary muffin or muesli bar mid-morning.

Dealing with bloating

Bloating and excess gas is a common complaint amongst those who eat a lot of beans and lentils. However - proper food preparation can help improve the digestibility and reduce unwanted side effects. Avoid tinned legumes and try and cook them from scratch, soaking in water with a dash of apple cider vinegar or lemon juice for 8 hours or more before cooking. This reduces the oligosaccharides that are readily fermented in the small intestine once eaten, causing bloating. When cooking, add a sprinkle of fennel seed, ginger or cumin - these are termed carminatives in Herbal Medicine and are well know for settling the stomach and reducing gas.

5 OF MY FAVOURITE PROTEIN-PACKED RECIPES:

- Creamy Spinach & Buckwheat Risotto

- Holy Moly Lasagna

- Ginger, Sesame & Maple Marinated Tempeh

- Kitchari - An Ayurvedic Healing Dish

- Nourishing Red Lentil & Rosemary Soup

Conclusion

Plant based diets can certainly provide adequate protein, with the caveat that one eats a variety of plant foods, including legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds. Generally speaking, whole grains lack the amino acid lysine, while legumes lack methionine. It was once thought that you had to combine these foods at the same meal in order to make a complete protein, however, we now know that’s not true. Favouring plant protein over animal protein in your diet comes with health benefits, and may help reduce risk of heart disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. It is also associated with lower mortality. Excess animal protein may lead to osteoporosis and kidney disease, but at this point in time, evidence is inconclusive.

This is part of a series on plant based nutrition. If you enjoyed the article and learnt something new, please feel free to share. Sign up to my newsletter below to get the series in your inbox as they come. My plan is to post these fortnightly.

Lauren.

In The Series:

References:

-

Whitney, E., Rolfes, S., Crowe, T., Cameron-Smith, D., Walsh, A. (2014). Understanding nutrition. Australia and New Zealand edition (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Cengage Learning

-

Gropper, S.S., & Smith, J.L. (2013). Advanced nutrition and human metabolism (6th, pp 481-500). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth

-

Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. (2014). Retrieved from https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients/protein

-

Bettelheim, F.A., Brown, W.H., Campbell, M.K., & Farrell, S.O. (2010). Introduction to general, organic, and biochemistry. Belmont, CA: Books/Cole

-

USDA National Nutrient Database. (2016). Full report (all nutrients): 11667, seaweed, spirulina, dried. Retrieved from https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/3306?n1=%7BQv%3D1%7D&fgcd=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=50&sort=default&qlookup=spirulina&offset=&format=Full&new=&measureby=&Qv=1

-

USDA National Nutrient Database. (2016). Full report (all nutrients): 12012, seeds, hemp seed, hulled. Retrieved from https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/3614?n1=%7BQv%3D1%7D&fgcd=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=50&sort=default&qlookup=hemp+seeds&offset=&format=Full&new=&measureby=&Qv=1

-

USDA National Nutrient Database. (2016). Full report (all nutrients): 12006, seeds, chia seeds, dried. Retrieved from https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/3610?n1=%7BQv%3D1%7D&fgcd=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=50&sort=default&qlookup=chia+seeds&offset=&format=Full&new=&measureby=&Qv=1

-

USDA National Nutrient Database. (2016). Full report (all nutrients): 20137, quinoa, cooked. Retrieved from https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/6587?n1=%7BQv%3D1%7D&fgcd=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=50&sort=default&qlookup=quinoa&offset=&format=Full&new=&measureby=&Qv=1

-

USDA National Nutrient Database. (2016). Full report (all nutrients): 20008, buckwheat. Retrieved from https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/6479?n1=%7BQv%3D1%7D&fgcd=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=50&sort=default&qlookup=buckwheat&offset=&format=Full&new=&measureby=&Qv=1

-

USDA National Nutrient Database. (2016). Full report (all nutrients): 20001, amaranth grain, uncooked. Retrieved from https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/6473?n1=%7BQv%3D1%7D&fgcd=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=50&sort=default&qlookup=amaranth&offset=&format=Full&new=&measureby=&Qv=1

-

Marsh, K.A., Munn, E.A., & Baines, S.K. (2012). Protein and vegetarian diets. MJA Open, 2, 7-10. Doi: 10.5694/mjao.11492

-

Schaafsma, G. (2000). The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score. The Journal of Nutrition, 130(7), 1865S-1867S.

-

Davey, G.K., Spencer, E.A., Appleby, P.N., Allen, N.E., Knox, K.H., & Key, T.J. (2003). EPIC-Oxford: Lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutrition, 6(3), 259-268. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002430

-

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, National Health and Medical Research Council; New Zealand Ministry of Health (2005). Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand including recommended dietary intakes. Canberra: NHMRC

-

Ball, M.J., & Bartlett, M.A. (1999). Dietary intake and iron status of Australian vegetarian women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(3), 353-358. Retrieved from http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/70/3/353.long

-

Wang, Y., & Beydoun, M.A. (2009). Meat consumption is associated with obesity and central obesity among US adults. International Journal of Obesity, 33(6), 621-628. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.45

-

Alkerwi, A., Sauvageot, N., Buckley, J.D., Donneau, A-F., Albert, A., Guillaume, M., & Crichton, G.E. (2015). The potential of animal protein intake on global and abdominal obesity: Evidence from the Observation of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Luxembourg (ORISCAV-LUX) study. Public Health Nutrition, 18(10), 1831-1838. Doi: 10.1017/S136890014002596

-

Shang, X., Scott, D., Hodge, A., English, DR., Giles, GG., Ebeling, P.R., & Sanders, K.M. (2016). Dietary protein from different food sources, incident metabolic syndrome and changes in its components: An 11-year longitudinal study in healthy community-dwelling adults. Clinical Nutrition. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.09.024

-

Feskens, E.J., Sluik, D., & van Woudenbergh, G.J. (2013). Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications. Current Diabetes Reports, 13(2), 298-306. doi: 1007/s11892-013-0365-0.

-

Slujis, I., Beulens, J.W.J., van der A, D.L., Spijkerman, A.M.W., Grobbee, D.E., & van der Schouw, Y.T. (2010). Dietary intake of total, animal, and vegetable protein and risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-NL Study. Diabetes Care, 33(1), 43-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1321

-

Song, M., Fung, T.T., Hu, F.B., Willet, W.C., Longo, V.D., Chan, A.T., & Giovannucci, E.L. (2016). Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(10), 1453-1463. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4182.

-

Dhillon, J., Craig, B.A., Leidy, H.J., Amankwaah, A.F., Anguah, K.O-B., Jacobs, A., …& Tucker, R.M. (2016). The effects of increased protein intake on fullness: A meta-analysis and its limitations. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(6), 968-983. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2016.01.003

Zara

Cannot thank you enough for this post. I'm currently trying to switch to a meatless diet and honestly, have no idea where to start or what to eat. This post has and will be so helpful, will be reading the rest in the series today also. X

Ascension Kitchen

Thanks Zara I'm glad you've found it helpful with the transition!

Hannah Phoebe Bowen

oh dear! this isn't the first time i've had the realisation that I'm not eating anywhere near enough protein! I managed to ignore it last time, and for years, but it's a rather stark reminder that I'm not looking after myself. I'm actually not eating a very good/balanced diet at ALL these days. thanks for reminding me

Ascension Kitchen

Be gentle with yourself sister! This has been a revealing process for myself also!

Rosie

I have loved reading the articles in the series, especially as i recently became vegan. I've also been learning more about macros and this came in handy for calculating my recommended vs actual protein intake. Thanks for creating this series!

Ascension Kitchen

Pleasure Rosie - I have so much more coming so it's nice to hear you are finding them valuable 🙂